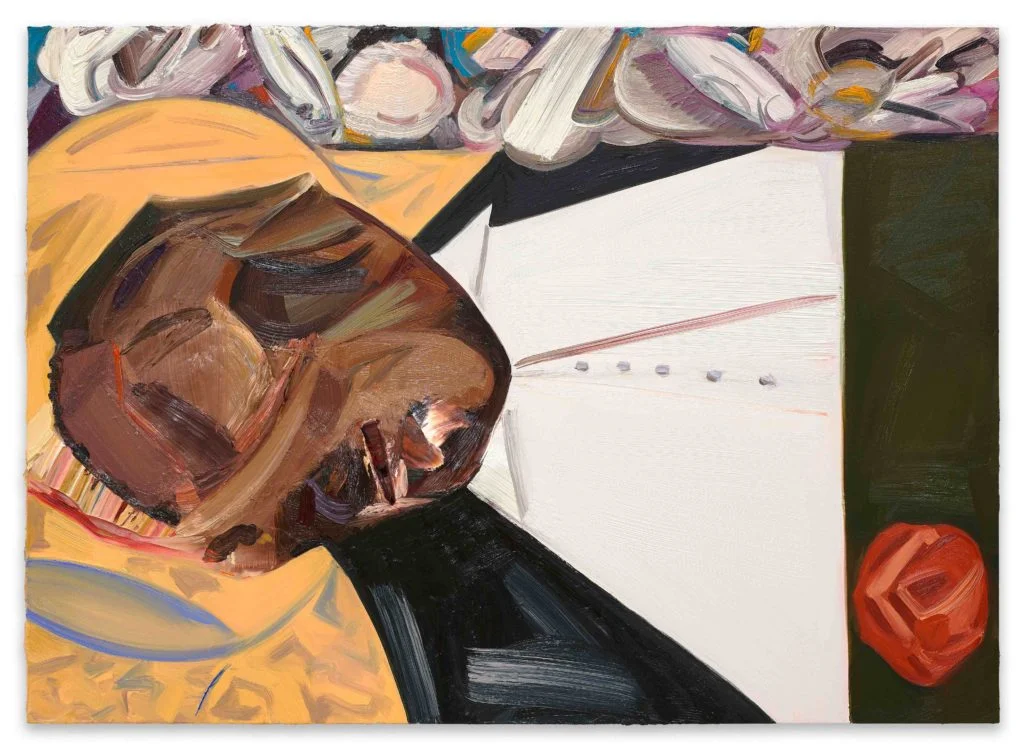

Dana Schutz Painting Of Emmett Till Creates Controversy At Whitney Biennial 2017

/The 2017 Whitney Biennial -- the first to take place at the museum's new headquarters in Manhattan's meatpacking district -- has received considerable praise as being uplifting and well-balanced. It's generally agreed that the Biennial has learned lessons from bitter past controversies over race and representation.

As always, some pundits consider the Biennial too tame. Writing for The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl observes:

The result, which is earnestly attentive to political moods and themes, already feels nostalgic. Most of the works were chosen before last year’s Presidential election. Remember back then? Worry, but not yet alarm, permeated the cosmopolitan archipelago of new art’s creators, functionaries, and fans. Now there’s a storm. The Age of Trump erodes assumptions about art’s role as a barometer—and sometime engine—of social change. Radicalism has lurched to the right, and populist nationalism, though it has had little creative influence so far, challenges sophisticated art’s presumption to the crown of American culture. The crisis makes any concerted will to “resist” awkward for those whose careers depend on rich collectors and élite institutions, sitting ducks for plain-folk resentment. Of course, artists are alert to ironies. The near future promises surprising reactions and adaptations to the new world disorder. But, for now, all former bets are off. The ones placed by the Biennial’s curators, Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, preface an unfolding saga in which, willy-nilly, all of us are characters.

Hannah Black Raises Her Fist For Emmett Till

UK-born, Berlin-based artist Hannah Black has registered a particularly strong dissent against one painting included in the Whitney Biennial, launching a campaign demanding that Biennial curators Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks remove Dana Schutz’s painting 'Open Casket' from the show, and calling for its destruction. (In a bit of irony, another painting by Schutz 'Elevator' is the featured photo in the New Yorker review.)

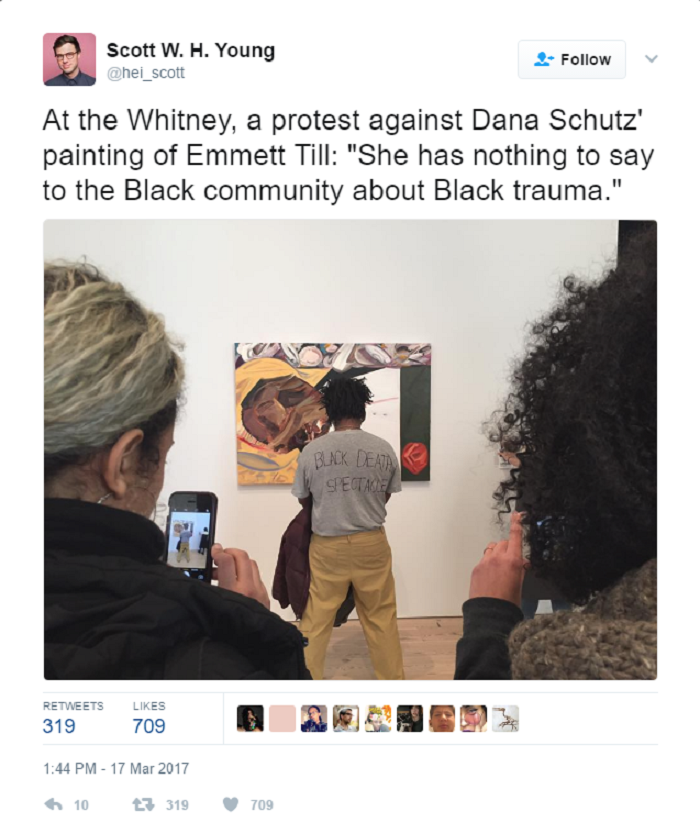

A small-scale protest of five or six people took place last Friday—when the Biennial first opened to the public— blocking the view of the painting from anyone who wanted to view it.

The painting is inspired by a photograph of the funeral of Emmett Till, an African-American boy who was viciously murdered at age 14 by two white men JW Milam and his half-brother Roy Bryant in Mississippi in 1955.

The Emmett Till Story

ArtNet writes that Till had been falsely accused of flirting with a white woman, a charge that is disputed presently by Till's cousin who says that Till did whistle at the woman Carolyn Bryant -- and nothing more. The Root explains:

In the Deep South, where racism was still violent as well as pervasive, Bryant and Milam took it upon themselves to abduct the young teen. They later admitted to killing Emmett, beating and mutilating him, shooting him to death and then sinking him in a local river. Emmett’s mother insisted on having an open-casket funeral for her disfigured son so that the world could witness the brutality of white supremacy.

The details of the Emmett Till case are front and center in America, with the 2017 publication of a new book 'The Blood of Emmett Till', authored by Timothy Tyson, a Duke University senior research scholar, who determined that in 2007, the white woman 'victim', now Carolyn Bryant Donham admitted that she had made up the majority -- and the most damning passages -- of her testimony in the murder trial.

Vanity Fair covers the story, previously published on AOC. Donham herself approached Tyson having admired Tyson’s earlier book, 'Blood Does Sign My Name', about another racism-inspired murder committed by someone known to Tyson’s family.

Schutz’s painting is a medium-sized canvas depicting Till’s face and chest, as he lies in his coffin. artnet News’ Christian Viveros-Fauné was impressed with the work, calling it a “powerful painterly reaction to the infamous 1955 funeral photograph of a disfigured Emmett Till,” adding that “the canvas makes material the deep cuts and lacerations portrayed in the original photo by means of cardboard relief.”

Hannah Black is having none of it!

Black wants the painting destroyed, considering it to be so exploitative that it should never be displayed in other institutions or sold in the art market.

"It's not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun," Black argues.

Like ArtNet, we publish her open letter to the Biennial curators in full:

To the curators and staff of the Whitney Biennial:

I am writing to ask you to remove Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum.

As you know, this painting depicts the dead body of 14-year-old Emmett Till in the open casket that his mother chose, saying, “Let the people see what I’ve seen.” That even the disfigured corpse of a child was not sufficient to move the white gaze from its habitual cold calculation is evident daily and in a myriad of ways, not least the fact that this painting exists at all. In brief: The painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.

Although Schutz’s intention may be to present white shame, this shame is not correctly represented as a painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist—those non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material. The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.

Emmett Till’s name has circulated widely since his death. It has come to stand not only for Till himself but also for the mournability (to each other, if not to everyone) of people marked as disposable, for the weight so often given to a white woman’s word above a Black child’s comfort or survival, and for the injustice of anti-Black legal systems. Through his mother’s courage, Till was made available to Black people as an inspiration and warning. Non-Black people must accept that they will never embody and cannot understand this gesture: The evidence of their collective lack of understanding is that Black people go on dying at the hands of white supremacists, that Black communities go on living in desperate poverty not far from the museum where this valuable painting hangs, that Black children are still denied childhood. Even if Schutz has not been gifted with any real sensitivity to history, if Black people are telling her that the painting has caused unnecessary hurt, she and you must accept the truth of this. The painting must go.

Ongoing debates on the appropriation of Black culture by non-Black artists have highlighted the relation of these appropriations to the systematic oppression of Black communities in the US and worldwide, and, in a wider historical view, to the capitalist appropriation of the lives and bodies of Black people with which our present era began. Meanwhile, a similarly high-stakes conversation has been going on about the willingness of a largely non-Black media to share images and footage of Black people in torment and distress or even at the moment of death, evoking deeply shameful white American traditions such as public lynching. Although derided by many white and white-affiliated critics as trivial and naive, discussions of appropriation and representation go to the heart of the question of how we might seek to live in a reparative mode, with humility, clarity, humor, and hope, given the barbaric realities of racial and gendered violence on which our lives are founded. I see no more important foundational consideration for art than this question, which otherwise dissolves into empty formalism or irony, into a pastime or a therapy.

The curators of the Whitney Biennial surely agree, because they have staged a show in which Black life and anti-Black violence feature as themes, and been approvingly reviewed in major publications for doing so. Although it is possible that this inclusion means no more than that blackness is hot right now, driven into non-Black consciousness by prominent Black uprisings and struggles across the US and elsewhere, I choose to assume as much capacity for insight and sincerity in the biennial curators as I do in myself. Which is to say—we all make terrible mistakes sometimes, but through effort the more important thing could be how we move to make amends for them and what we learn in the process. The painting must go.

Thank you for reading,

Hannah Black

Artist/writer

Whitney Independent Studies Program 2013–14

Hannah Black has posted the letter on Facebook, modified to allow Black co-signs only, while encouraging non-Blacks to help get the painting destroyed in other ways. The Whitney as issued an update:

UPDATE

Statement from the Whitney Biennial curators, Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, sent to artnet News:

“The 2017 Whitney Biennial brings to light many facets of the human experience, including conditions that are painful or difficult to confront such as violence, racism, and death. Many artists in the exhibition push in on these issues, seeking empathetic connections in an especially divisive time. Dana Schutz’s painting, Open Casket (2016), is an unsettling image that speaks to the long-standing violence that has been inflicted upon African Americans. For many African Americans in particular, this image has tremendous emotional resonance. By exhibiting the painting we wanted to acknowledge the importance of this extremely consequential and solemn image in American and African American history and the history of race relations in this country. As curators of this exhibition we believe in providing a museum platform for artists to explore these critical issues.”

W Magazine interviews curators Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks in Whitney Biennial 2017: How the Riskiest, Most Political Survey in Decades Came Together.

We will update this article as new views are expressed on this critical subject of 'cultural appropriation' in the creative disciplines.